Produced by John Congleton, ‘All of Us Flames’ unleashes Ezra Furman’s songwriting in an open, vivid sound whose boldness heightens the music’s urgency.

Ezra Furman can feel the future barreling toward the now. Inside the world of her new album, All of Us Flames, the end of the patriarchal capitalist empire seems both imminent and inevitable, a turn down a path we can’t see yet but can’t avoid, either. The heat of a different world throbs just behind the skin of this one; all around us, openings to it flicker. They vanish almost as soon as they’ve appeared. But they keep appearing, as if daring us to hold them open, to widen them until they turn into a way.

A singer, songwriter, and author whose incendiary music has soundtracked the Netflix show Sex Education, Furman has for years woven together stories of queer discontent and unlikely, fragile intimacies. She has a knack for zeroing in on the light that sparks when struggling people find each other and ease each other’s course. All of Us Flames widens that focus to a communal scope, painting transformative connections among people who unsettle the stories power tells to sustain itself.

Produced by John Congleton in L.A., All of Us Flames unleashes Furman’s songwriting in an open, vivid sound world whose boldness heightens the music’s urgency. The record arrives as the third installment in a trilogy of albums, beginning with 2018’s Springsteen-inflected road saga Transangelic Exodus and continuing with the punk rock fury of 2019’s Twelve Nudes.

“This is a first person plural album,” Furman says. “It’s a queer album for the stage of life when you start to understand that you are not a lone wolf, but depend on finding your family, your people, how you work as part of a larger whole. I wanted to make songs for use by threatened communities, and particularly the ones I belong to: trans people and Jews.”

She wrote much of Flames during the early months of the pandemic. “I had no time alone anymore; my house was super crowded,” she says. She drove to seek solitude, parked in arbitrary quiet spots around Massachusetts, and began to write. The songs that came flowed toward ideas of communality and networks of care, systems of survival cultivated by necessity among people who have been historically deprived of them.

Furman took inspiration from Bob Dylan’s ’80s albums, whose tone she describes as “a little bitter and a little hopeful,” as well as the collective ferocity of ’60s girl groups, particularly the Shangri-Las and the Ronettes. “I listened to ‘Dressed in Black’ by the Shangri-Las hundreds of times,” she notes. “When I was writing, I read that Mary Weiss of the Shangri-Las carried a gun in her purse on tour. There’s such violence to being a girl or a woman. It’s all gotta be cute, all the time, and also people are trying to kill you. And that’s life, the feminine life. Plus, young lovers just want to destroy the world.”

In her own song, also called “Dressed in Black,” Furman dreams of running away with a lover to forge a world away from the one that wants to kill them. The synth-streaked rallying call “Forever in Sunset” peers past the scorch of the apocalypse into a vision of collective survival, tracing the ways outcast people can make each other real through mutual belief. “We’ve been alone too long / We belong together with our weapons drawn,” she sings on “Lilac and Black,” a revenge plot where she and her “queer girl gang” drive out their oppressors and claim a hostile city for themselves.

“I started to think of trans women as a secret society across the world: scattered everywhere, but so obviously bound together, both in being vulnerable and having a shared vision to change a fundamental building block of patriarchal society,” she says. “I’ve been building my world of queer pals, and it feels like we’re forming a gang.”

The soulful sweep of “Point Me Toward the Real” sets Furman’s voice against cascades of backing vocals (performed by Shannon Lay and Debbie Neigher) and horns (arranged by Bright Eyes’ Nathaniel Walcott) — a warm backdrop for tales of trauma, care, and healing to unfurl. On “Poor Girl A Long Way From Heaven,” Furman recounts a childhood encounter with God, a gesture of spiritual yearning that flows into the album’s biblical facets.

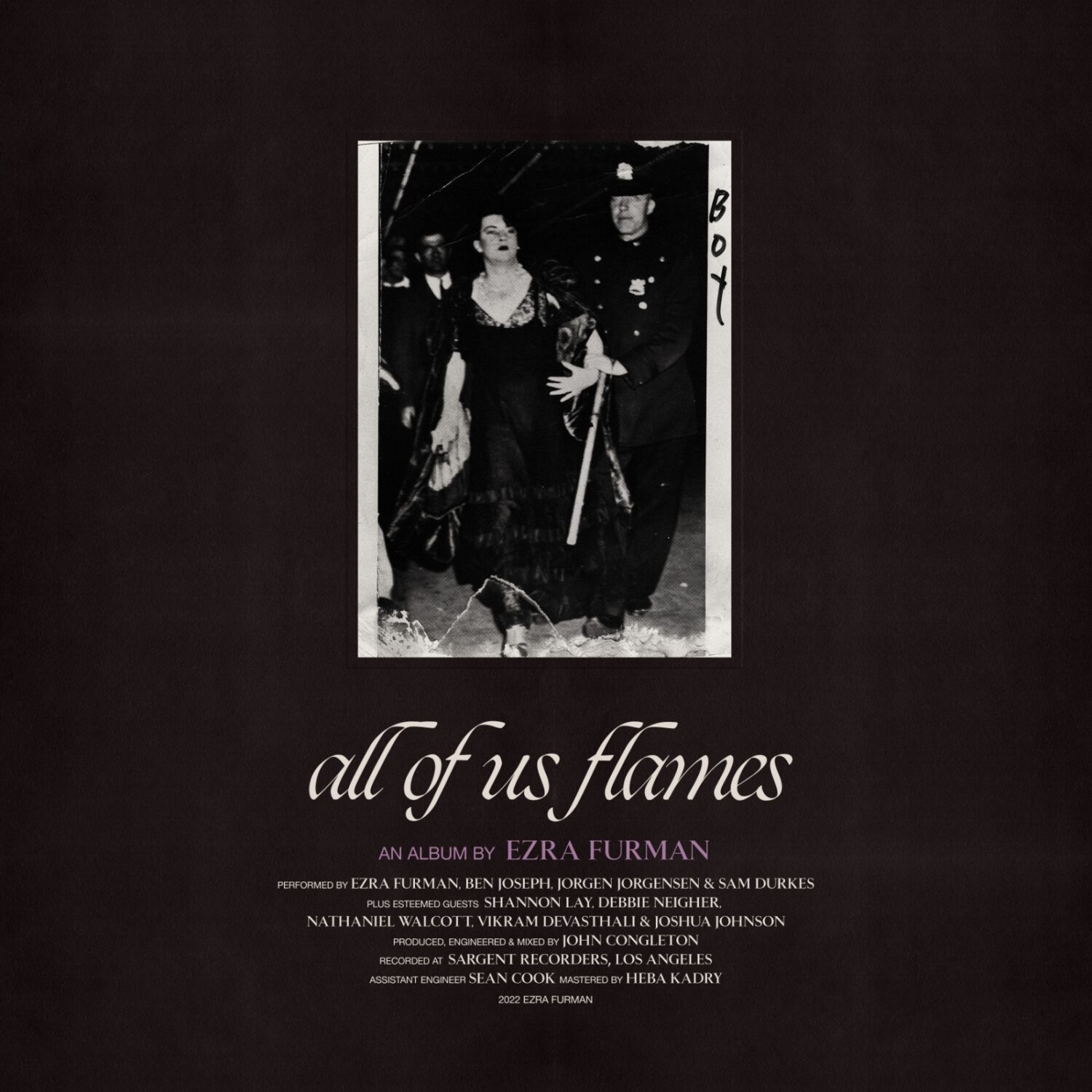

The video is a story Ezra made up about a trans Joan of Arc avoiding her public execution, and was directed by Haoyan of America and available to view HERE.

“The album is more biblically informed than politically informed,” Furman says. “The truth, both current and ancient, is that the rich are allowed to kill the poor. Despised people get their lives ruined or taken as a matter of course. The Bible is obsessed with lifting up the weak. People who don’t matter are God’s main concern.”

The LP’s title derives from a lyric in the song “Book of Our Names,” inspired by the second book of the Hebrew Bible: “I want there to be a book of our names / None of them missing / None quite the same / None of us ashes / All of us flames.”

“We don’t want the world as it was given to us. What do we want? What do you build in the space you cleared by fire?” Furman asks. “After you purge all that is false, you have a positive yearning for what’s real.” There’s a place where we make it — where people who have been cast aside, abused, and exploited in service of power can claim names for themselves, where they can speak them aloud together in safety and peace. No one gets there alone. Without each other — without the collective spirit Furman invokes in her expansive, searing vision — we can’t even seek the way.

Listen to All Of Us Flames HERE

Next In Next In

⇥ 10 Albums that Marked February 2023